Same old govt, new economic path?

Proposing four key reforms to transform the nation’s economic landscape

Author: Zeeshan Hashim

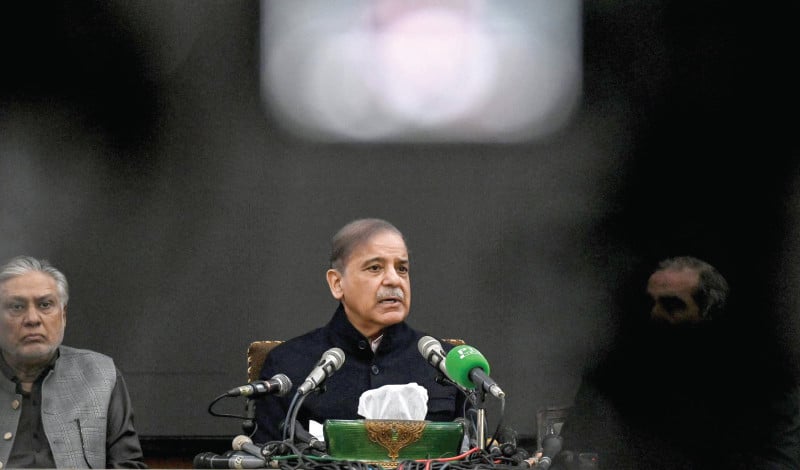

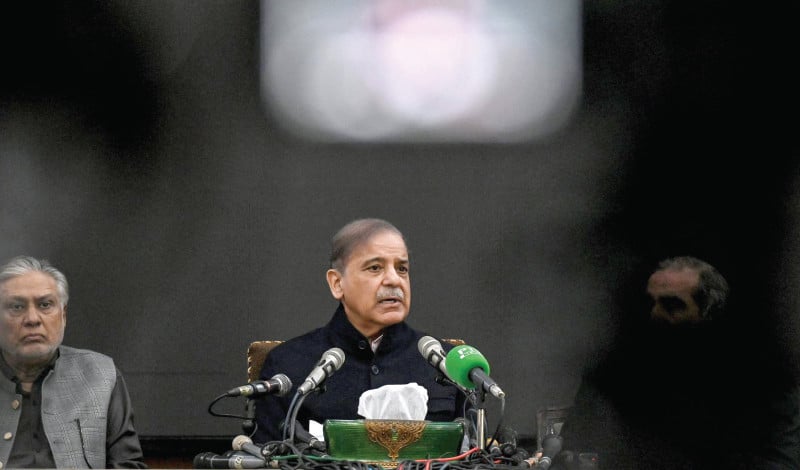

Pakistan held a general election on February 8th, 2024, and the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) formed its government on March 4th, 2024. Mian Shehbaz Sharif, who led the previous government under the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) coalition, is the current prime minister.

However, according to major macroeconomic indicators like inflation, growth rate, and unemployment, the performance of the PDM government hasn’t been impressive.

When PDM assumed office in April 2022, the economy was not functioning well. Rather than pursuing structural reforms that could bring long-term gains, the government decided to maintain the status quo and stabilise the economy using conventional tools that have a long history of failure. As a result, almost two years have passed, and the economic situation remains dire.

The new government may repeat past mistakes, but good hope remains for economic reforms. In this article, I propose four major reforms that can benefit the economy in the long run.

Firstly, rationalising the current economic model is a complex but necessary task. The model has failed and will only produce the same results if it remains in its present form. It has weak institutions, relies on debts and remittances, has an uncompetitive industrial structure, declining exports, brain drain, a lower tax base, economic uncertainty, regulatory burden, and a large government size.

To survive, the government is raising taxes at the cost of savings, consumption, and citizens’ welfare.

It is necessary to audit the entire economic structure, analysing what works and what does not, and removing all inefficiencies.

Without it, no policy is effective since these inefficiencies are deeply embedded in the present model. This long, continuous process needs improvement at each stage but must be done as soon as possible.

Secondly, creating state institutions that ensure the rule of law and accountability.

It also requires a strong political commitment despite high political costs to the dominant state institutions that maintain the status quo. They may prefer to keep their present position. But if they are concerned about the country’s development, they must not create barriers to institutional reforms.

Thirdly, we require market-led reforms that facilitate the growth of the private sector in the market. The private sector is the main driving force behind economic development, job creation, tax revenue, lower inflation, and an improved standard of living for the citizens. A stronger market paves the way for a stronger economy.

Unfortunately, doing business in Pakistan is not easy due to various factors. Some are institutional, such as corruption and regulatory burdens, while others are structural, such as a lower comparative advantage in the competitive market. To address these issues, we need institutional reforms to tackle the former and industrial policy to address the latter.

My fourth suggestion is about industrial policy. It doesn’t involve creating a further government footprint in the market while eliminating some. Its economic justification is simple: internalising externalities to capture learning and innovation and offsetting those externalities that cause market failure. Its objective is to promote industrial development to improve productive capacity and diversification in the economy and to facilitate some industries to gain a comparative advantage in the local and international markets. It will ultimately increase the market size and boost the export sector.

Regarding industrial policy, the most influential economist, Dani Rodrik, warns, “The kind of discipline that’s required is the discipline of monitoring, figuring out whether what you’re doing is working, and being able to move away from mistakes when things aren’t working. Successful industrial policy is not about picking winners; it’s about letting the losers go. Some of the worst cases of industrial policy are when you keep putting good money after bad.”

Therefore, before starting the industrial policy, Pakistan must ensure its policymakers and political economy are efficient enough to maintain that discipline Rodrik advises. Otherwise, a new industrial policy will create new evils.

Almost all industrialised countries, including East Asian economies, have achieved economic success due to the abovementioned factors. These are not easy to implement and require strong political commitment, which is why not all countries are successful economically.

However, the evidence confirms that these policies work and have contributed to the economic success of many countries.

THE WRITER IS A RESEARCH SCHOLAR AT THE PRIME INSTITUTE, A DOCTORAL RESEARCHER AT BRUNEL UNIVERSITY AND A LECTURER OF ECONOMICS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF BEDFORDSHIRE