Setting the stage

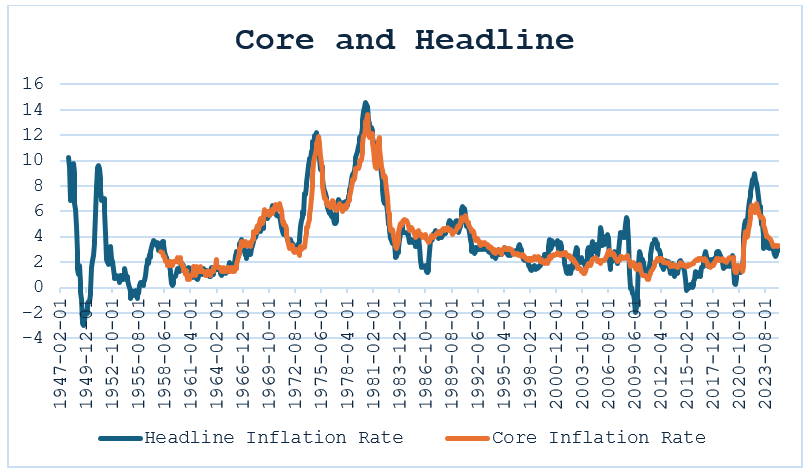

The 2021-2022 inflation was an extraordinary event. One of the reasons it became special and a subject of interest for economists was that it succeeded COVID-19, which combined features of both a demand and supply-side shock. The Russia-Ukraine that started in Feb 2022 became the basis of a commodity super cycle that sent inflationary shockwaves to nearly all major economies in the world, including the US where CPI inflation peaked at 9.1% in June 2022. However, the uniqueness of this event was not in the making of inflation but rather in the manner in which it tapered-off starting FY 2023.

As geopolitical tensions rise again, it is important for central banks to rationalize their inflationary expectations, and understand the mechanics of inflation, particularly its supply-side antecedents, to make a pre-emptive approach and draw up monetary policy responses that can navigate the impending challenge of inflation. In the current inflationary round, the supply-side dynamics may couple with, or be compounded by a tariff regime that is setting in within major import markets of the world. Tariffs will have both inflationary and distortionary impacts, but for this note, I’d focus on inflation alone and the circumstances that led to the 2021-2022 episode, and raise a few points of caution for the policy-maker.

Figure.1. Core and Headline Inflation

Source: FRED and author’s own calculations

The Classic Phillips Curve for the US

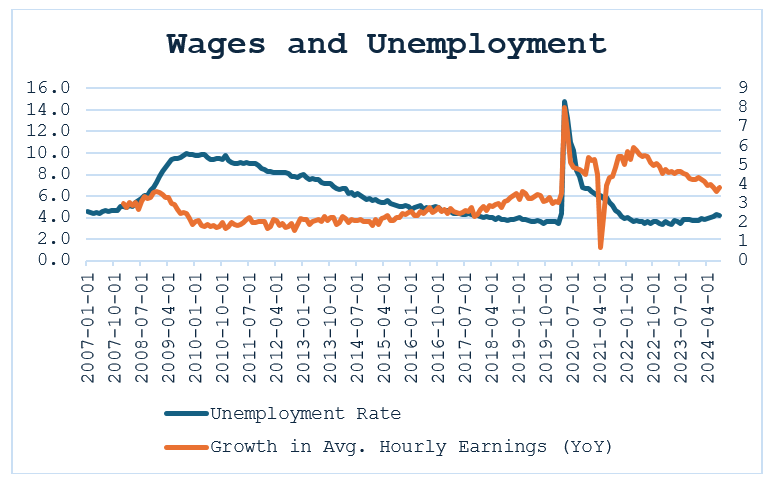

When inflation was rising rapidly in 2021, it was predicted that a sustained period of high unemployment would be required to bring inflation back to the Federal Reserve’s 2% target. Such predictions closely aligned with the findings of the classic Phillips curve that hypothesizes the presence of a trade-off between inflation and unemployment. However, inflation has declined significantly without a notable rise in unemployment. Unemployment declined steadily after peaking at around 14.8% in March, 2020. It remained low, fluctuating between 3.6% and 3.9% through 2021 and 2022 which is a good starter to the discussion about the 2023 disinflation being cost-free – was it?

The big question that the preceding context raises is whether the economists overestimated the persistence of supply-side shocks and the sensitivity of inflation to unemployment. The empirical evidence favors the notion that the Phillips curve was flatter indicating a low sensitivity of inflation to changes in unemployment, and the fact that inflation expectations were strongly anchored around the 2% target. There predictive models were wrong as the economists failed to account for the supply-side antecedents of inflation. In the discussion below, I would attempt to fill the missing parts of the inflation puzzle and highlight factors that led to the discrepancy between the actual costs of disinflation versus costs estimated by the economic analysts.

Figure.2. Wage Growth and Unemployment Rates in the US

Source: FRED and author’s own calculations

Discussion

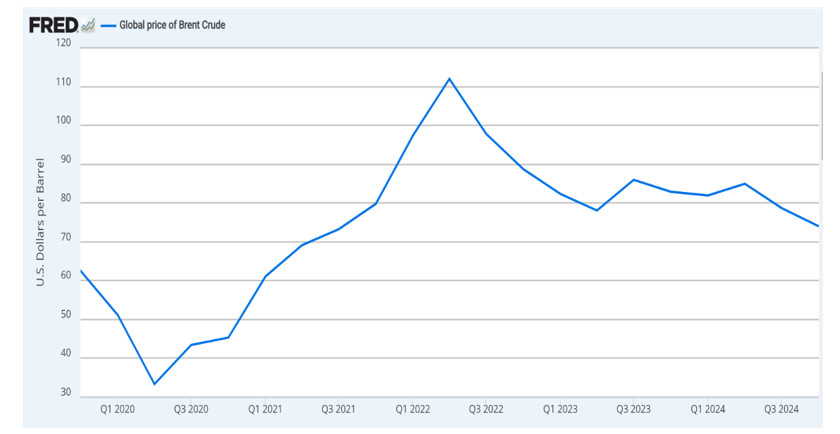

Supply-chain disruptions and energy price shocks were less persistent than anticipated. This reduced inflationary pressures without requiring higher unemployment to cool demand. Energy prices dropped significantly from over $120/barrel in June 2022 to $70-$90/barrel in late 2023. Global supply chain pressures also normalized by mid-2023. Economists missed the mark when it came to the duration of such shocks. The 70s experience did favor longer supply-shocks that had an unemployment cost associated with disinflation. It would be interesting to dig deeper into this to analyze if unemployment would have risen eventually and persisted at those levels if energy prices continued to rise or stay at higher levels?

Figure.3. Brent Crude Price

Source: FRED

The labor market showed signs of resilience as return of the workers to the labor market kept wage growth at moderate to low levels despite low unemployment. The macroeconomic theory indicates that in a low unemployment environment, wage growth would be high as firms would have to pay more to extract effort. However, such pressures on wages, that are usually characteristic of low unemployment, were averted by factors including labor hoarding by firms, and return of workers to the labor market after COVID-19. Wage growth (year-over-year growth in average hourly earnings) decelerated from 5.9% in March 2022 to 4.3% in Oct 2023 indicating easing labor market pressures, and lower rate of inflation without an accompanying employment sacrifice.

High credibility of the FED was assistive in anchoring inflation expectations around the FED target of 2%. Fed’s credibility coupled with an aggressive communication strategy seems to have set in an expectations regime that limited second-round effects from wage-price spirals (wage growth = price growth). This is an outcome of the fundamental policy shift from adaptive to anchored inflation expectations. An inflation-targeting central bank and anchoring of inflation expectations were theoretical constructs prior to the 2021-2022 inflation, however, the ideas came to life as unemployment remained near historic lows while inflation tapered-off as measured by the 5-year breakeven inflation rates that remained stable around 2%.

Policy Implications

One of the critical lessons for policymakers is to stop looking away from supply-side dynamics. They must account for the transitory nature of supply shocks in future inflation forecasts and avoid banking too heavily on demand-side measures. The supply-side dynamics can be a good starting point of the conversation about monetary policy tightening as policymakers can attempt to rule out the possibility of a supply-driven inflation before they throw resources at the prospect of disinflation through an interest-rate hike.

Secondly, one can also identify the need to revisit some of the modelling assumptions and findings of the Phillips curve which is necessary to vindicate the theoretical relationship between unemployment and inflation in very special situational contexts. Some questions that can be considered are whether the standard assumptions and findings of the Phillips curve hold in the case of supply-side shocks and see if this relationship changes when the supply-side shock is accompanied, or preceded by a demand-side dynamic. So, it could be argued that traditional models may overstate the trade-off between unemployment and inflation which necessitates revision of frameworks to reflect structural changes in the economy.

In the nutshell, the following implications for policymakers are salient:

Conclusion

The 2021-2022 inflation was different to the stagflation experienced by the US economy in the 1970s. The 1970s stagflation is a useful comparator as growth was low and inflation rose rapidly. But the missing piece of the puzzle on this occasion was unemployment that did not rise as much as it did in the 70s. Price volatility was slower and inflation did not persist. This provides credence to the argument that some analysts made about inflation being ‘transitory’ which, Ed Dolan (2023) argues is self-reinforcing as the claims that it is transitory are always heard, putting downward pressure on prices.

The decline in inflation without a rise in unemployment underscores the importance of incorporating supply-side dynamics and expectations anchor into macroeconomic policy. This episode offers lessons for responding to future inflationary episodes with minimal economic disruption.

References

Dolan, E., & Dolan, E. (2023, February 6). The inflation of 2021-22 was different: what we

should learn from it – Niskanen Center. Niskanen Center – Improving Policy, Advancing Moderation. https://www.niskanencenter.org/the-inflation-of-2021-22-was-different-whatwe-should-learn-from-it/

Burki, S., Chowdhury, I. A., & Butt, A. (Eds.). (2019). Pakistan at seventy: A handbook on developments in economics, politics and society. Routledge.

Butt, A. E. (2022). Pakistan’s Fatiguing Interest in the IMF Reform Program’. South Asian Voices.

OnLabor. (2021, December 17). Wages and prices are rising – Is the Phillips curve back? OnLabor. https://onlabor.org/wages-and-prices-are-rising-is-the-phillips-curve-back/

Asad Ejaz Butt is an economist based in Boston, USA. His research interests are in the areas of global wealth inequalities, debt and taxation and international capital flows.