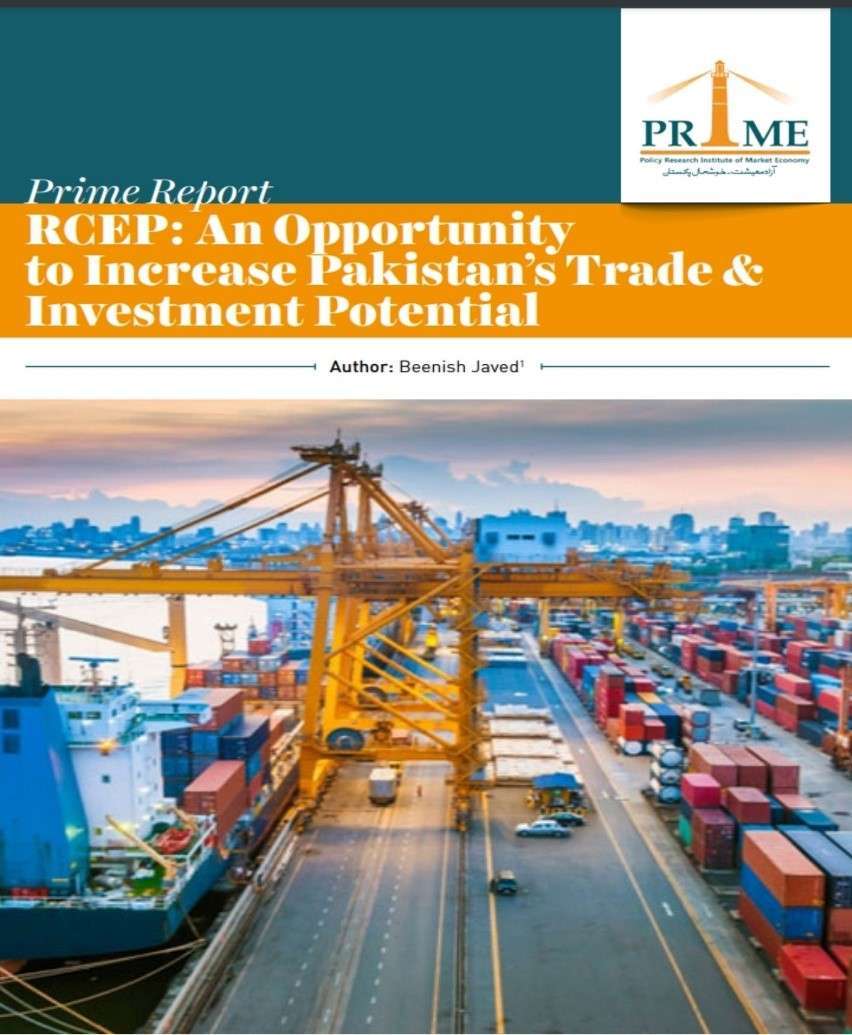

RCEP: Opportunity to increase Pakistan’s Trade & Investment

PRIME’s latest report timely informs of a window of opportunity – the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – offering immense trade and investment potential. RCEP links 15 Asia Pacific countries (accounting for 30% of the global GDP) through a Free Trade Agreement (FTA). The report establishes a strong case for Pakistan’s accession to the RCEP with logical arguments, grounded in the incumbent government’s mandate