مڈل مین بارے بدگمانی چھوڑئیے

مصنف: علی سلمان

مڈل مین ہر اُس لعن طعن کا سزاوار نہیں ٹھہرتا جو اُس پر دوش ڈالی جاتی ہے ۔

نوٹ:- یہ تحریر اصل انگریزی تحریر کا ماخوذ اردو ترجمہ ہے ۔ اصل انگریزی متن کی تحریر انگریزی جریدے دی ایکسپریس ٹربیون میں 10مئی 2021ء کو شائع ہوئی تھی ۔

پاکستان کے اقتصادی پالیسی ساز حلقوں کی تدبیروں اور عامیانہ بحثوں میں اقتصادی چیلنجز بارے مستقل طور پر جو لکیر پیٹی جاتی ہے وہ مڈل مین کا کردار ہے جسے اکثر و بیشتر بے جا طور پر مارکیٹ کی حرکیات میں تمام تر برائیوں کا محور سمجھا جاتا ہے ۔

ہر ایک اقتصادی سیکٹر میں مڈل مین اور ڈسٹریبیوٹر کا کردار ناگزیر ہوتا ہے ۔ غور کیجیے کہ کون کپڑوں کو فیکٹریوں سے دکانوں میں پہنچاتا ہے؟ یہ بحث زرعی منڈی کی حرکیات میں نسبتاً زیادہ آسانی سے سمجھی جاسکتی ہے ۔

مڈل مین بارے یہ بدگمانی دیکھنے کو ملتی ہے کہ وہ کسان اور صارفین دونوں کا استحصال کرتا ہے اور اپنے پیوستہ مفادات میں اجتماعی فلاح، اخلاقی اقدار اور مستعد کارکردگی کے تقاضوں کو نظرانداز کرکے ناجائز منافع اینٹھتا ہے ۔

مڈل مین بارے مخبوط رویہ رکھنے کے کارِ لاحاصل نے اقتصادی پالیسی سازوں کے ساتھ ساتھ مبصرین کی توانائیاں بھی نامناسب حد تک سلب کرلی ہیں اور اُن کی صلاحتیں دائرہ ءِ عمل سے خارج بے سروپا حل تجویز کیے جانے تک اٹکی ہوئی ہیں ۔

ایسے ناقابلِ حصول قسم کے سلجھاءو کا مدعا کبھی عیاں اور کبھی پنہاں الفاظ میں مڈل مین کے کردار کو ختم کیے جانے کا متقاضی ہوتا ہے اور وہ بھی اِس خودفریبانہ امید پر مبنی ہوتا ہے کہ مڈل مین کو ختم کرتے ہی قیمتیں کم ترین سطح پر آجائیں گی ۔

امید ہے کہ مدعائے مضمون یہ گوش گزار کرواپائے گا کہ مڈل مین جسے ہم نے ناسمجھی میں ’’شیطانِ مجسم‘‘ سمجھ رکھا ہے کا معاملہ ’’بد اچھا بدنام برا‘‘ والا ہے اور یہ کہ مڈل مین ہر اس لعنت و ملامت کا قصوروار نہیں ہے جو اُس کے سر تھوپی جاتی ہے ۔ درحقیقت معاشیات کی معقول معاملہ فہمی رکھنے والا کوئی بھی شخص جو کشادہ نظری سے حقائق سننے کو تیار ہو وہ معاشی حرکیات کا ادراک کرلینے کے بعد ہماری روزمرہ کی زندگی میں مڈل مین کے کردار کو سراہنے لگے گا ۔

کسی پریکٹس بارے تھیوری ہر اُس کے لیے رہنما ہونی چاہیے جو اُس کی اہمیت سمجھتا ہو ۔ مسلمانوں میں ایک مذہبی پیشوا امام غزالی نے ڈیوڈ ریکارڈو سے آٹھ صدیوں قبل ’مسابقتی منفعت‘ کی تھیوری کا ادراک کرلیا تھا جو یہ بتاتی ہے ’’ ۔ ۔ ۔ کسانوں کی کثرت زرخیز علاقوں میں ہوتی ہے جہاں زرعی آلات تیار نہیں کیے جاتے جبکہ اُوزار ساز لوہار ترکھان کاریگر وہاں ہوتے ہیں جہاں کسان نہیں ہوتے ۔ لہٰذا فطری طور پر ایک دوسرے کی ضروریات کی بہم رسانی کے لیے وہ آپس میں اشیاء و خدمات کا تبادلہ کرتے ہیں ‘‘ ۔

ایک ہی زمان و مکان میں کسان کھیتی باڑی کرنے کے ساتھ ساتھ آڑھتی نہیں بن سکتا اور ہر صارف بھی روزانہ کھیتوں میں جاکر منڈی سے سستے نرخ پر سبزیاں نہیں خرید سکتا؛ لہٰذا ایسے میں مڈل مین کی ضرورت پڑتی ہے جو کسان اور صارف میں وسیلہ بننے کی مشقت اٹھائے اور خود کو رِیسک کے جوکھم میں ڈال کر اپنا منافع کمائے ۔

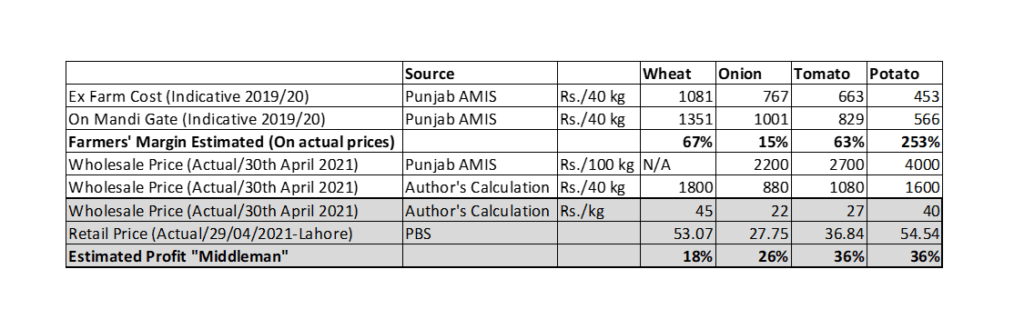

جو قارئین اس تھیوری کو سمجھ یا اس پر اعتماد نہیں کرسکتے اُن کے لیے تعاملاتی شواہد سے اخذ کردہ ڈیٹا پیش ہے ۔ حکومتِ پنجاب زراعت بارے ایگریکلچر مارکیٹنگ انفارمیشن سروس (اے ایم آئی ایس) کا محکمہ چلارہی ہے جہاں نرخ بندیوں کا ڈیٹا تواتر کے ساتھ مرتب کیا جاتا ہے ۔

یہ محکمہ ’اے ایم آئی ایس‘ متعدد اجناس کی نقد فصلوں کی قیمتوں میں مرحلہ وار چڑھاءو کے اشاریے مرتب کرتا ہے جیسا کہ کٹائی شدہ فصل کا بھاؤ تاؤ، غلہ منڈی میں تھوک کی بولی لگنا اور پرچون کی دکانوں میں صارفین کے لیے نرخ بندی طے پانا ۔ یعنی کہ فصل سے دکان اور کسان سے صارف تک کے نرخ بندی کے تخمینوں کے اعدادوشمار مرتب کرتا ہے ۔

اس محکمہ کے لاگت اور منافع جات کی مد میں مرتب کردہ اعدادشمار تجاویزی نوعیت کے ہیں ۔ ان اعدادوشمار کا موازنہ کبھی بھی پاکستان کے محکمہ شماریات (پی بی ایس) کے مرتب کردہ مروجہ قیمتوں کے اعدادوشمار سے کیا جاسکتا ہے ۔ اس طرح سے، جو کوئی بھی فصل کے نرخوں کا منڈی کے نرخوں سے موازنہ کرنے کے بعد بالآخر پرچون سے موازنہ کرے گا وہ اس معاشی سرگرمی سے کسان اور مڈل مین کے کمائے گئے منافع میں تفاوت کا تناسب با آسانی سمجھ سکے گا ۔

زرعی اشیائے خوردونوش کی طلب اور رسد کا توازن یعنی ’’فوڈ باسکٹ‘‘ جس کے تحت صارفین کے لیے قیمتوں کا اشاریہ یعنی کنزیومر پرائس انڈیکس (سی پی آئی) ترتیب پاتا ہے میں 20اشیاء شامل ہیں ۔ اس اشاریے کے مطابق 70فیصد غذائی اخراجات 20فیصدی نچلے درجے کی آمدن والے گھریلو صارفین کی جانب سے بلحاظِ اخراجاتی ترتیب سات اقسام کی اشیائے خردونوش کھلا دودھ، آٹا، آلو، پیاز، ٹماٹر، چکن اور کوککنگ آئل کی مَدّوں میں کیے جاتے ہیں ۔

راقم الحروف نے اپنے تجزیے میں گندم اور تین جنس کی سبزیوں کے ڈیٹا سے استفادہ کیا تھا جو کہ ایگریکلچر مارکیٹنگ انفارمیشن سروس پنجاب(اے ایم آئی ایس) اور ادارہِ شماریاتِ پاکستان (پی آئی بی) سے لیا گیا تھا ۔ یہاں ضمناً ایک احتیاطی نکتہ سپلائی چین کے جاری سلسلے بارے مختلف سطح کی تقابلی قیمتوں سے متعلق ذیل میں دیا جارہا ہے جسے ملحوظِ خاطر رکھا جائے ۔

زرعی منڈی کی حرکیات خصوصاً جب وہ نرخ بندی اور تجارتی قیود کی پابندیوں کے زیرنگرانی ہوں تو ایسے میں وہ باقی منڈیوں کے برعکس زیادہ شدت کے ساتھ اتارچڑھاءو دکھانے پر مجبور ہوتی ہیں لہٰذا تخمینہ کاری میں عمومی رائے اپنانے کی بجائے احتیاط برتنے کی ضرورت ہوتی ہے ۔

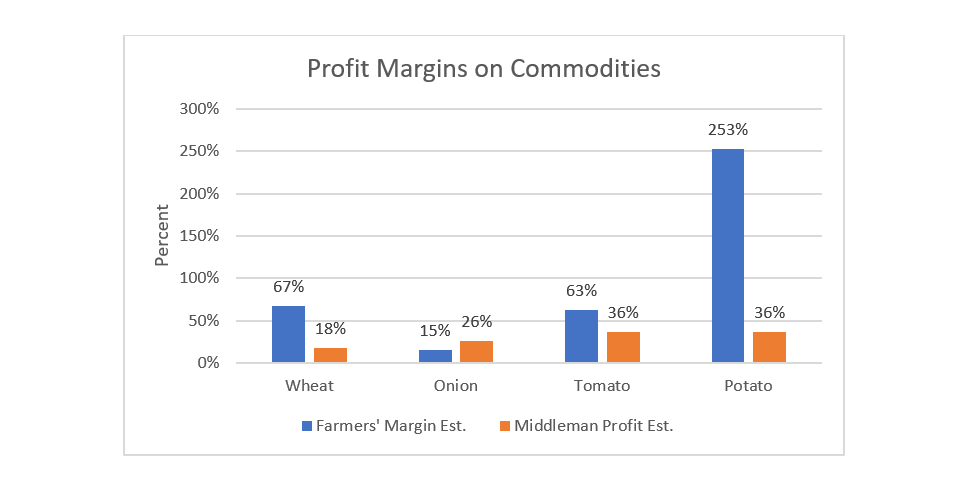

اگر مڈل مین کے کردار کا تجزیہ تھیوری کے ساتھ ساتھ اعدادوشمار کی روشنی میں بھی کرلیا جائے تو یہ ثابت ہوجائے گا کہ نہ تو مڈل مین ہتھیانے والا استحصالی ہوتا ہے اور نہ ہی کسان منافع سے محروم رکھا گیا لاچار مفلس ہوتا ہے ۔ ثبوت میں ذیل میں دیا ڈیٹا دیکھیے ۔

مثلاً سال2020ء-2021ء کے دوران گندم، پیاز، ٹماٹر اور آلو کی نقد فصلوں میں کسانوں کے کمائے گئے منافع کا تخمینہ15فیصد سے 253فیصد کی پہنچ تک کا تھا ۔ اس کے برعکس مڈل مین کے منافع کی پہنچ 18فیصد سے 36فیصدتک کی معمولی سطح کی تھی ۔ درحقیقت اگر آپ گہرائی سے دیکھیں تو کسان اور مڈل مین میں منافع کے تفاوت کا یہ حاشیہ تھوک اور پرچون کی متضاد سطحوں پر خریدوفروخت سے ماخوذ ہے ۔ اس سے یہ نتیجہ نکلتا ہے کہ کسان کا کسی ایک سال میں غیرمعمولی منافع کما پانا اور کسی دوسرے سال میں بھاری نقصان اٹھانا دونوں صورتوں کے امکانات معمول کا معاملہ ہوتے ہے ۔ جو کوئی بھی دیہی معیشت کی سمجھ بوجھ رکھتا ہو اس کو یہ اتار چڑھاءو سمجھ میں آ سکتا ہے ۔

اسی طرح مڈل مین کا منافع نپی تلی سطح پر اس لیے رہتا ہے کہ اُسے فصلوں کی کٹائی کے بعد غلہ گوداموں میں رکھنے اور طلب کے مطابق بیچنے میں نسبتاً کم رِسک لینا پڑتا ہے ۔ یہی تو اقتصادیات ہے ۔ اس میں حکومت کو کیا کرنا چاہیے؟ زیادہ تر معاملات میں حکومت کو کوالٹی چیک اور ادارہ جاتی سطح پر معاہداتی تقدس اور تحفظاتی اقدامات کے سوا مزید کچھ نہیں کرنا چاہیے ۔

درحقیقت مڈل مین کو استحصالی سمجھنا ایک غلط العام وسوسہ ہے ۔ مڈل مین کو استحصالی کہہ کر ہم صرف اپنی من گھڑت اختراع کا اظہار کرتے ہیں ۔ جب تک منڈی کی حرکیات ہر خاص و عام کے لیے کھلی ، آزاد اور مسابقتی رہیں گی تب تک استحصال معاشی عمل کے خودرو بہاءو سے مسدود ہوتا رہے گا ۔

مڈل مین کا کردار معاشی لین دین میں محور کی حیثیت رکھتا ہے ۔ ٹیکنالوجی کو مڈل مین کا متبادل خیال کرتے وقت ہ میں یہ ادراک کرنا ہوگا کہ یہ تبدیلی وساطت کی تنسیخ پر منتج نہیں ہوسکے گی البتہ وسیلہ بننے والے کردار کی تبدیل کرپائے گی ۔ مثلاً آڑھت کے ناگزیر عمل میں آڑھتی کا عامل کردار اب تک کوئی کارندہ کرتا آرہا ہے وہی عمل ورچوئل پلیٹ فارمز کے میکانی کرداروں سے کروائے جانے کی تجویز ہے جس کا نتیجہ اسی قدر یا زیادہ منافع ورچوئل پلیٹ فارمز کو دینا ہوگا ۔

اگر حکومت کسانوں اور صارفین میں براہ راست تعلق کے لیے مارکیٹیں قائم کرنے جارہی ہے تو وہ صرف ہمارے قیمتیں نہ دیکھ پا سکنے کے امرِ مانع کی خصوصیت کی بنا پر آزاد نہیں قرار دی جاسکتیں۔

تشویش کی بات یہ ہے کہ ایسا کرکے حکومت نے وہ بار اٹھایا ہے جسے کرنے کی نہ تو وہ متحمل ہے اور نہ ہی اس کا کوئی لینا دینا ۔ ایسا کرکے حکومت اپنے کرنے کے بنیادی اور لازمی کاموں کو پس پشت ڈال چکی ہے ۔