Cost of welfare policy

Ali Salman

Welfare is not free as someone always pays cost of this system

ISLAMABAD: Welfare is an elusive term. Politicians talk about welfare all the time and seek votes on the basis of providing welfare to the masses.

There is a popular concept of a welfare state, which supposedly can take care of the masses, say through the provision of unemployment allowance or subsidies or food.

However, it is obvious that despite being packaged as free, or subsidised, welfare is not free. Someone always pays the cost of this welfare.

It’s a question of resource allocation and market structures who gets benefits and who pays costs. Academically speaking, welfare economics deals with this and considers policies which can maximise benefits for all or most members of a society.

Distribution of welfare usually takes the form of allocation of resources towards a specific component of population.

Take one example – the subsidy or concession for housing loans. Ownership of houses has become difficult for the present generation, which increasingly comprises nuclear families.

In a recent PIDE publication, the popular notion of shortage of 10 million houses is contested, citing 70% home ownership at the national level as per PSLM 2019-20.

However, the government has announced a programme of constructing or facilitating the construction of five million houses. Following this target, the government announced various fiscal and monetary incentives in an effort to correct “market failures”.

It announced a major amnesty scheme to attract investment in real estate. It also set mandatory lending targets for commercial banks.

To date, with Rs38 billion disbursed, the Mera Pakistan Mera Ghar financing scheme has benefited not more than 10,000 households.

On the other hand, prices of land, which takes as much as 80% of the cost of a house in a city, have risen by 60% for everyone in cities like Lahore and Islamabad in just two years.

This has resulted from an unusual flow of capital in real estate – according to a recent news report, as much as $19 billion has been buried in empty urban plots in 2021 alone.

This is the direct consequence of a policy defined by tax exemptions and fiscal subsidies.

Lesson 1: The welfare policy in the name of poor people has benefited a few thousands while causing losses to millions of people.

A majority of households would have benefited in the absence of these incentives and especially through reforms in building regulations.

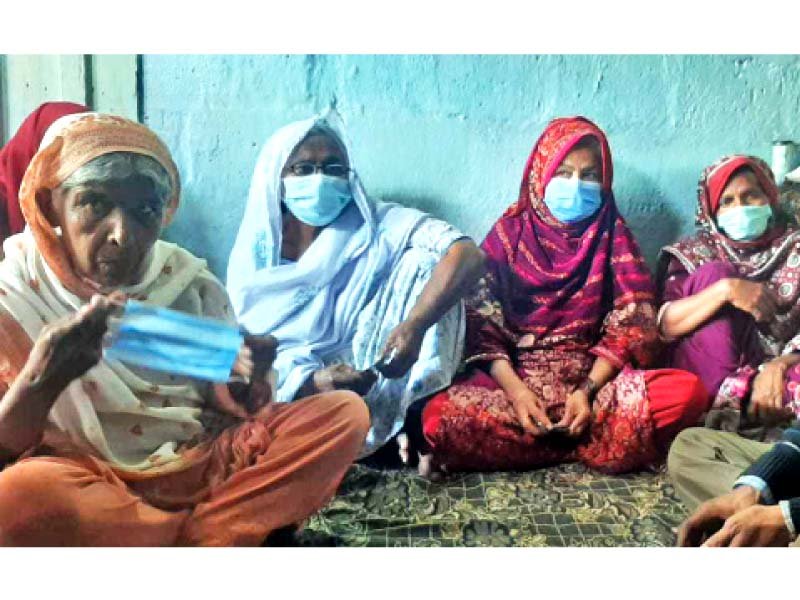

Another example of welfare policy is the universal health insurance – the Sehat Sahulat Card, which has provided Rs1 million medical insurance to all eligible citizens in Punjab and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

This has been generally lauded by all. However, with a careful look – and as some time passes by – the problems in the universal medical insurance will become clear.

The government will find it impossible to fund the programme on its own very soon while the public health system will deteriorate.

A differently designed health protection programme would have led to the flow of greater investment in the public healthcare system.

A small admission fee is affordable by all and should be charged without exception. The government should have left insurance to be managed by the private sector.

This is how resource allocation and adjustment with market structures can work to maximise welfare for most of the population at the least cost.

Lesson 2: A universal and publicly funded health insurance is a bad idea and the government can achieve more by investing in the public healthcare system.

Another popular example of a welfare policy is price control. The prime minister and federal cabinet keep monitoring prices of fruits and vegetables – with noble intentions.

The government has established price control committees and hired more price inspectors than before.

Prices are only going up. If the government were to focus on a two-pillar strategy – invest in agricultural productivity and allow border trade, it would have provided both short-term and long-term solutions.

On the other hand, price controls have made sure no one invests in agriculture, thus undermining the major goal of keeping prices low.

Price controls provide clear signals to investors and traders – do not enter into the business.

Lesson 3: Price controls distort welfare.

Welfare policies must be put to a simple theoretical question of efficiency and incentives. To bring in welfare economics once again, one can look at the economic surplus – the sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus.

I will also add a fiscal equation here given our constraints and would caution against any policies becoming a fiscal burden.

As three examples above indicate, in each case, welfare policies have distorted incentives and have contributed to the reduction of welfare in fact. This is why, it is very difficult to design a welfare programme which can ensure increase in the overall welfare without greater loss.

A wiser option for a government may be actually do no welfare at all, especially if it poised to do more harm than good.

The writer is the executive director of PRIME, an independent economic policy think tank based in Islamabad

Published in The Express Tribune, February 28th, 2022.