فلاحی پالیسی کی قیمت

فلاح و بہبود مفت ہرگز نہیں ہے کیونکہ ہمیشہ کوئی اس فلاحی نظام کی قیمت ادا کرتا ہے۔

مصنف : علی سلمان

فلاح و بہبود ایک بے معنی اصطلاح ہے۔ سیاست دان ہر وقت فلاح و بہبود کی باتیں کرتے ہیں اور عوام کی فلاح و بہبود کی بنیاد پر ووٹ مانگتے ہیں۔

فلاحی ریاست کے معروف تصور کے مطابق بے روزگاری الاؤنس یا سبسڈی یا خوراک کی فراہمی کے ذریعے عوام کا خیال رکھ سکتی ہے۔

تاہم، یہ واضح ہے کہ ان تمام چیزوں کی فراہمی کو مفت ظاہر کرنے ، یا سبسڈی دینے باوجود ، فلاح و بہبود مفت نہیں ہے۔ کسی نہ کسی کو ہمیشہ اس فلاح و بہبود کی قیمت ادا کرنا پڑتی ہے۔

یہ وسائل کی تقسیم اور مارکیٹ کی ساخت کا سوال ہے کہ کون فوائد حاصل کرتا ہے اور کون ان کی قیمت ادا کرتا ہے۔ علمی لحاظ سے، 'فلاحی معاشیات 'اس سے نمٹتی ہے اور ایسی پالیسیوں پر غور کرتی ہے جو معاشرے کے تمام یا زیادہ تر اراکین کے لیے زیادہ سے زیادہ فوائد مہیا کر سکیں ۔

فلاح و بہبود کی تقسیم عام طور پر آبادی کے ایک مخصوص حصے کے لیے وسائل کی تقسیم کی شکل اختیار کرتی ہے۔

مثال کے طور پر - گھر کے قرضوں (ہاؤسنگ لون ) کے لیے سبسڈی یا رعایت۔ خاص کر نیو کلیئر خاندانوں پر مشتمل موجودہ نسل کے لیے مکانات کی ملکیت مشکل ہو گئی ہے ۔

پائیڈ (PIDE) کی ایک حالیہ اشاعت میں، پاکستان سوشل اینڈ لیونگ سٹینڈرڈز سروے ( PSLM 2019-20) کے مطابق قومی سطح پر 70% گھروں کی ملکیت کا حوالہ دیتے ہوئے، 10 ملین گھروں کی کمی کے معروف تصور کا جواب دیا گیا ہے۔

تاہم حکومت نے 50 لاکھ گھروں کی تعمیر یا سہولت فراہم کرنے کے پروگرام کا اعلان کیا ہے۔ اس ہدف کے بعد، حکومت نے "مارکیٹ کی ناکامیوں" کو درست کرنے کی کوشش میں مختلف مالیاتی اور مالی مراعات کا اعلان کیا۔

حکومت نے رئیل اسٹیٹ میں سرمایہ کاری کو راغب کرنے کے لیے ایک بڑی ایمنسٹی اسکیم کا اعلان کیا۔ اس نے کمرشل بینکوں کے لیے لازمی قرضے کے اہداف بھی مقرر کیے ہیں۔

آج تک، 38 ارب روپے تقسیم کیے گئے، میرا پاکستان میرا گھر فنانسنگ اسکیم سے 10,000 سے زیادہ گھرانوں کو فائدہ نہیں پہنچا۔

دوسری طرف، زمین کی قیمتیں، جو کہ ایک شہر میں ایک گھر کی قیمت کا 80 فیصد لیتی ہیں، صرف دو سالوں میں لاہور اور اسلام آباد جیسے شہروں میں سب کے لیے 60 فیصد تک بڑھ گئی ہیں۔ یہ سب رئیل اسٹیٹ میں سرمائے کے غیر معمولی بہاؤ کے نتیجے میں ہوا ہے - ایک حالیہ خبر کے مطابق، صرف 2021 میں ہی خالی شہری پلاٹوں میں 19 بلین ڈالر کی سرمایہ کاری دفن ہو چکی ہے۔

یہ ٹیکس کی چھوٹ اور مالیاتی سبسڈیز کے ذریعے بیان کردہ پالیسی کا براہ راست نتیجہ ہے۔

سبق 1: غریبوں کے نام پر دی گئی فلاحی پالیسی سے چند ہزار کو فائدہ ہوا جبکہ لاکھوں افراد کو نقصان ہوا۔

ان مراعات کی غیر موجودگی میں اور خاص طور پر تعمیری ضوابط میں اصلاحات کے ذریعے گھرانوں کی اکثریت مستفید ہو سکتی تھی ۔

فلاحی پالیسی کی ایک اور مثال یونیورسل ہیلتھ انشورنس ہے - صحت سہولت کارڈ، جس نے پنجاب اور خیبرپختونخوا ہ میں تمام اہل شہریوں کو 10 لاکھ

روپے کا طبی انشورنس فراہم کیا ہے۔

عام طور پر اس کی سب نے تعریف کی ہے۔ تاہم، ایک محتاط نظر کے ساتھ –

اور جیسے جیسے کچھ وقت گزرے گا – یونیورسل میڈیکل انشورنس میں مسائل واضح ہو جائیں

گے۔ حکومت کیلئے بہت جلد اس پروگرام کو خود سے فنڈز دینا ناممکن ہو جائے گا جبکہ صحت عامہ کا نظام

خراب ہو جائے گا۔ صحت سے متعلق تحفظ کا ایک مختلف پروگرام صحت عامہ کے نظام میں زیادہ

سرمایہ کاری کا باعث بن سکتا تھا ۔

ٹوکن فیس کے طور پر ایک چھوٹی اور

معقول رقم سب کے لیے قابل برداشت

ہے اور اسے بغیر کسی استثنا کے ہر ایک سے وصول کیا جانا چاہیے۔ حکومت کو انشورنس کا نظام

سنبھالنے کیلئے پرائیویٹ سیکٹر کو ذمہ داری سونپنی چاہئے تھی ۔

اس طرح وسائل کی تقسیم اور مارکیٹ کی ساخت کے ساتھ ایڈجسٹمنٹ،

کم از کم قیمت پر زیادہ تر آبادی کی فلاح

و بہبود کے لیے کام کر سکتی ہے۔

سبق 2: یونیورسل اور عوامی طور پر فنڈ شدہ ہیلتھ انشورنس ایک ناقص خیال ہے اور حکومت پبلک ہیلتھ کیئر سسٹم میں

سرمایہ کاری کر کے مزید بہتر نتائج حاصل

کر سکتی ہے۔

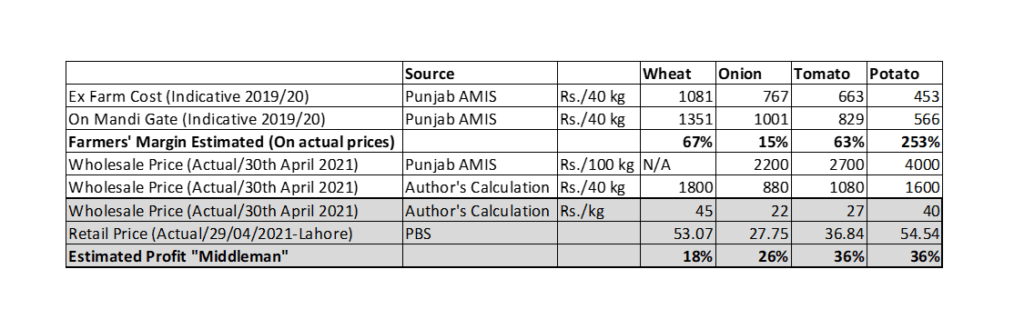

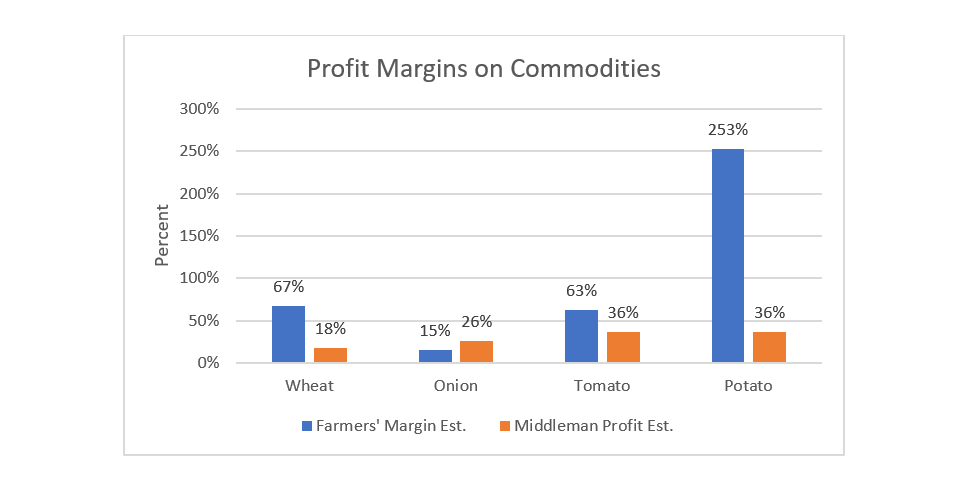

فلاحی پالیسی کی ایک اور معروف مثال قیمت کو کنٹرول کرنا ہے۔ وزیراعظم اور وفاقی کابینہ اچھے ارادوں

کے ساتھ پھلوں اور سبزیوں کی قیمتوں کی

نگرانی کرتے رہتے ہیں۔

حکومت نے قیمت کنٹرول کرنے کیلئے کمیٹیاں

قائم کی ہیں اور پہلے سے زیادہ پرائس انسپکٹرز کی خدمات حاصل کی ہیں۔

قیمتیں صرف بڑھ رہی ہیں۔ اگر حکومت نے دو ستونوں والی حکمت عملی پر توجہ مرکوز کرنا

تھی تو - زرعی پیداوار میں سرمایہ کاری کرتی اور سرحدی

تجارت کی اجازت دی جاتی ، تو اس سے ہمیں قلیل

مدتی اور طویل مدتی حل فراہم ہو سکتے تھے ۔

دوسری طرف، قیمتوں کے کنٹرول نے اس بات کو یقینی بنایا ہے

کہ کوئی بھی زراعت میں سرمایہ کاری نہ کرے، اس طرح قیمتیں کم رکھنے کے اہم ہدف کو نقصان پہنچا ہے۔

قیمتوں کا کنٹرول، سرمایہ کاروں اور تاجروں کو یہ واضح اشارہ فراہم کرتا ہے کہ – کاروبار میں داخل نہ ہوں۔

سبق 3: قیمتوں کا کنٹرول فلاح و

بہبود کو مسخ کرتا ہے۔

فلاح و بہبود کی پالیسیوں کو کارکردگی اور مراعات کے ایک

سادہ نظریاتی سوال پر رکھا جانا چاہیے۔ فلاحی معاشیات کو ایک بار پھر سے لانے کے لیے،

کوئی بھی معاشی سرپلس (صارفین کے سرپلس

اور پروڈیوسر سرپلس کا مجموعہ) کو دیکھ سکتا ہے ۔ میں اپنی رکاوٹوں کے پیش نظر یہاں ایک مالی

مساوات بھی شامل کروں گا اور کسی بھی پالیسی کے مالی بوجھ بننے کے خلاف احتیاط

کروں گا۔

جیسا کہ اوپر دی گئی تین مثالیں بتاتی ہیں، ہر معاملے میں

فلاحی پالیسیوں نے دی گئی مراعات کو مسخ کیا

ہے اور حقیقت میں فلاح و بہبود کو کم کرنے میں اہم کردار ادا کیا ہے۔ یہی وجہ ہے

کہ ایسے فلاحی پروگرام کو ڈیزائن کرنا بہت مشکل ہے جو زیادہ نقصان کے بغیر مجموعی

بہبود میں اضافہ کو یقینی بنا سکے۔

حکومت کے لیے ایک دانشمندانہ آپشن ہو سکتا ہے کہ کوئی فلاح

و بہبود ہرگز نہ کریں، خاص طور پر اگر وہ بہتری سے زیادہ نقصان پہنچانے کے لیے تیار ہوئی ہو ۔

مصنف اسلام آباد میں موجود ایک آزاد اقتصادی پالیسی تھنک ٹینک PRIME کے ایگزیکٹو

ڈائریکٹر ہیں۔

یہ مضمون ایکسپریس ٹریبیون میں 28 فروری 2022 کو شائع ہوا۔